Everyone starts somewhere. Scripting is not necessary for making games, but it can be extremely helpful to know just a little bit of programming, even if you don’t intend to become a programmer - you’ll have more insight into the coding mindset, which will help you communicate more effectively in a team. Or you do want to become a programmer, in which case, it’s time to get you up to speed on how scripting in Unity works. Introductory programming tutorials can be a little dry but stick with it and over time we’ll do more and more interesting things with code!

Unity Basics aims to teach you a little part of Unity in an easy-to-understand and clear format.

This tutorial is aimed at people who have never scripted/coded before, but may have some familiarity with the Unity Editor.

Also check out this tutorial on my YouTube channel if reading isn’t your thing:

What are scripts?

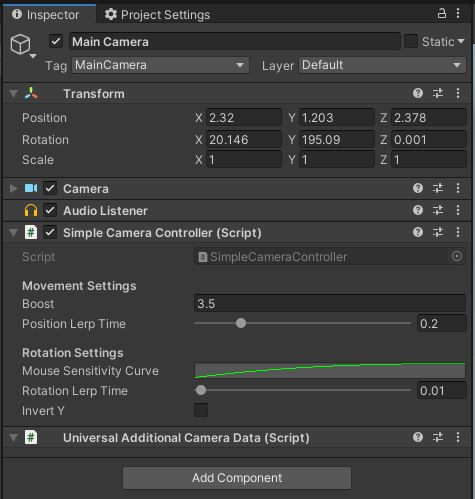

Scripts are used to make objects in your game do something. In Unity, a GameObject contains a list of Components, each of which are little bundles of behaviour that the GameObject can do - with scripting, we can create one of these Components. If I were to create a new Scene (by going to File -> New Scene) and select the default Main Camera (by left-clicking it in the Hierarchy), I might see something like this in the Inspector:

The Main Camera’s component list shows attached Transform, Camera, Audio Listener and Simple Camera Controller components.

The Main Camera’s component list shows attached Transform, Camera, Audio Listener and Simple Camera Controller components.

Those Components - Transform, Camera, and so on - are provided by Unity, and we can add our own via scripting. To create a new script, right-click in the Project View and select Create -> C# Script - we’re going to create a movement script, so name it “Movement”. Let’s go over the absolute basics. When you open the script (by double-clicking it, which should open it in Visual Studio by default), you’ll be presented with this template:

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using UnityEngine;

public class Movement : MonoBehaviour

{

// Start is called before the first frame update

void Start()

{

}

// Update is called once per frame

void Update()

{

}

}

Classes

You’ll notice that it’s put the name “Movement” inside the script, since that’s what we named the file. We’ll start with this line:

public class Movement : MonoBehaviour

There’s five important things here. Firstly, the name of the script: Movement. When we attach this to a GameObject in the Editor, that’ll be the name of the Component.

Secondly, the class keyword. A class is a bundle which contains the state of the script and some behaviour it may possibly perform. If I were to write a Daniel class, then my state would be “am sitting down”, “am typing”, “am thinking about gamedev”, and my possible behaviours might be “stand up”, “procrastinate on YouTube” or “eat pizza”. You get the idea. Everything contained in the pair of curly braces which start on the following line are contained in this class. It’s like a blueprint - if we need multiple Daniels, we create instances of the Daniel class, and they act independently, according to the blueprint we wrote.

Next, the public keyword. In coding, when we have two scripts that are interacting, there are some things we want another script to access, and other things we want to keep hidden. By making something public, generally, this means it’s accessible to other scripts. In Unity, this class must be public, or else we won’t be able to use it as a Component. The opposite is private, which prevents other scripts from accessing something. The public and private keywords are called access modifiers.

That leaves two things - the colon : and MonoBehaviour. We won’t go into too much detail about this, but classes can inherit certain characteristics from other classes. In Unity, MonoBehaviour is the base class for all scripts that you want to use as a Component, and the colon means “inherits from”. So Movement : MonoBehaviour means “Movement inherits from MonoBehaviour” or, more naturally, “Movement is a Component”. Phew, that’s a lot of concepts packed into just one line!

This is a tangent, but often I feel like one of the things that puts people off coding is the number of things that “will make sense later”. However, like a “real” language, programming languages have their own grammar which seems alien at first, but the more you write, the more it becomes natural, and before long, you’ll (hopefully) subconsciously begin “speaking” C# in your own head! If you need time to write code that breaks a lot before it clicks, that’s natural - and the advantage of Unity being so widely-used is that you can usually just Google an error message or code snippet and find that someone else treaded that ground already.

Namespaces

That wasn’t even the first line of the script - we skipped over a few. Now that we know what a class is, it’s useful to figure out what kind of features the class has access to. All C# scripts - regardless of whether we’re using Unity - have access to all the core C# features, but what about things that are specific to Unity?

using System.Collections;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using UnityEngine;

A namespace is, essentially, a collection of classes which do a similar thing. For example, if you wrote a bunch of classes related to databases, you might put them in a namespace called Databases. Similarly, the core Unity features - including the MonoBehaviour class - are in a namespace called UnityEngine. To use it, we have a handy keyword - using. The script template also includes two non-Unity C# namespaces, System.Collections and System.Collections.Generic, because they’re so commonly used in Unity scripts, but they’re not necessary for the default code to work. Those two namespaces contain classes that let us manage collections of data. You’ll rarely need to include other namespaces when you’re just starting out, and most tutorials will let you know when you do.

Variables (State)

We talked earlier about the state of a class. To represent that state, we use variables. We’re going to start writing our own code now, so do follow along at home! Let’s imagine we have a player character and we want them to have some amount of health. Start a new line after the opening curly brace after the class declaration we looked at earlier, then write the following line of code:

private int health = 100;

Earlier, we talked about private - it makes this variable only accessible to this class. Then we have a new keyword, int. In our example, health is an integer value between 0 and 100, and to represent integer (whole number) values, we use the int keyword. This is the type of the variable, and we must include this so that C# knows how much memory to reserve for this variable. Imagine it’s a box that’s exactly big enough to fit one integer number. Next, we’ve written health, which is the name of the variable. We could actually end the line here, which would initialise health with a default value of 0, but instead, we’re going to assign a value of 100 to it by writing = 100. And finally, in C#, we use a semicolon ; to end the statement.

Of course, int is not the only type of variable. C# has many built-in, or primitive, types that we can use:

private string name = "Ellen";

private bool tallerThanDan = true;

public float speed = 1.0f;

Let’s go over each of these. A string is a bunch of text. It can be a single word, a sentence, a paragraph, or even completely empty, and we define strings by writing text in a pair of quotes, as we have here with "Ellen". A bool, which is short for “Boolean”, is a variable which can be either true or false. We use variables like those in logical statements. And if we need non-integer numbers, we use floating-point numbers by using the float keyword. To define one of these, we put an f after the number - in this case, 1.0f. There are other types we haven’t covered here, but these ones should give you a good idea of the types of variable you can use.

If we want to use instances of a class in our code, we use the same syntax.

public GameObject cube;

In this example, we’re defining a variable named cube, whose type is GameObject. This tells C# that it should expect this variable to have all the state and behaviour of a GameObject (a class provided by Unity), and we’ll be able to access that object to change its state and cause it to do some behaviour. We’ll see how that works in the next section.

Methods (Behaviour)

Our script template also comes with the following code:

// Start is called before the first frame update

void Start()

{

}

// Update is called once per frame

void Update()

{

}

Start and Update are both methods. We write methods to encapsulate a list of commands, and later we can call those methods to execute that list of commands. As such, methods represent the behaviours the script can carry out. These two methods are inherited from the MonoBehaviour base class. The void keyword means that the method doesn’t return anything - it just carries out a list of commands, but it doesn’t send any data back to the code that called the method. We’re going to write some code in Update.

We want to move a cube by reading the player’s input. Unity provides a few ways to read input - we’ll be using the older input system. Inside the curly braces for this method, write these lines of code:

float x = Input.GetAxis("Horizontal");

float z = Input.GetAxis("Vertical");

You’ll probably recognise those as variables! But it’s slightly more complex now. We have two variables named x and z, both of which are float-type. We’re assigning values to both using =, but in both examples, we’re calling a method and assigning its return value to the variable. The Input class is specific to Unity, and it defines several methods for reading player input, including GetAxis, which is used to read input axes such as horizontal movement, vertical movement, and so on.

The syntax for calling a method is to write its name, then use parentheses to include a list of parameters - in this case, we need to pass in a string. The “Horizontal” and “Vertical” axes are already available by default and they’re the WASD keys or arrow keys on your keyboard. So, in effect: Unity is reading how much the A and D keys are pressed and returning a value between -1 and 1 to determine how far between left and right the player is pressing, and it’s doing the same with W and S for vertical movement.

Finally, to actually move our cube, we need to add this line after reading the input, but still inside the Update curly braces:

cube.transform.position += new Vector3(x, 0, z) * Time.deltaTime * speed;

There’s a lot happening here. On the left hand side, we’re taking our cube - which is a GameObject - and saying cube.transform to access the Transform component on the cube. Transform contains the position, rotation and scale of our cube. Then, we use transform.position to access the position of the cube. By using +=, we’re doing a shortcut: this takes whatever’s on the right-hand-side, adds it to what’s on the left-hand-side, then assigns its value back to the left-hand-side. So rather than overwriting the position, which = does, we’re adding to it.

On the right-hand-side, we need to create something that can be added to the position. Position is a vector in 3D space, and Unity provides a type called Vector3 to represent those. So to start off, we need to create a brand new Vector3 - and to do that, we need to use a keyword called new to assign space in memory for it. Then we need to tell it what values to use for its three components, so we pass in the x and z variables. This is a special type of method called a constructor, because it is called when we’re creating a new instance of that class and we can pass in data so that it has the correct initial values.

We’ve got a vector which represents which keys are being pressed, but we need to know how fast the player should move. Luckily, we added a variable called speed earlier, so we can multiply by that by using the * operator. Then the only thing left to consider is this: how often does the code get called? Unity runs Update every frame, but it has a variable framerate - so on slow computers, it might be called 30 times a second, but faster computers will run it at 60 times a second, and beyond. To ensure the cube moves the same distance, regardless of framerate, we need to multiply by 1 divided by the framerate. Unity provides that value in the Time class, in a variable called deltaTime.

Congratulations, you’re just written your first script!

Interacting in the Editor

Now that we’ve written the script, we need to attach it to an object. In the Unity Editor, we can left-click-drag the script from the Project View onto any one of the GameObjects in the Hierarchy - I added mine on a cube object I added from the toolbar via GameObject -> 3D Object -> Cube. On of Unity’s most powerful features is the ability to interact with code via the Editor, and when you attach this script, you’ll notice that there are two fields on the component named “Cube” and “Speed”. That’s because we made those two variables public, and Unity has taken their names, capitalised them, and placed them here, with boxes next to them where we can put things according to the variable’s type.

The Cube field requires a GameObject, so take the Cube from the Hierarchy and left-click-drag it onto the field. The cube is now, in fact, referencing itself; there are ways to do that purely inside the code, but I wanted to show you how to do it in-Editor. For the Speed field, we can just type in a value ourselves - something around 4 or 5 will do. If you press the Play button at the top of the Editor, you should now be able to use the WASD or arrow keys to move the cube around. It’s possible to tweak the Speed variable while the game is playing, but all changes will be reverted when you exit Play Mode - it’s great for non-destructive testing, but make sure you’re out of Play Mode if you’re making lots of changes you want to be permanent!

Conclusions

Scripting is powerful and you can do almost anything you want using it. We’ve gone over the most basic concepts of scripting in Unity and C# - what variables and methods are and how to use them - but to really get started with Unity, you will probably find it most useful to play around with adding code and hacking together things until they work, then armed with what you’ve learned, try something else and see if you can make something more complex! Don’t be shy to search online for examples and read the code to learn what it’s doing in detail, then use what you’ve learned in your own code.

Acknowledgements

Supporters

Support me on Patreon or buy me a coffee on Ko-fi for PDF versions of each article and to access certain articles early! Some tiers also get early access to my YouTube videos or even copies of my asset packs!

Special thanks to my Patreon backers for January 2021!

Gemma Louise Ilett

JP

Jack Dixon Tuomas Männistö

Chris Sims FonzoUA Jesper Kuutti MR MD HARDING Maya Nedeljkovich Moishi Rand Shaun Wall

Anna Voronova James Poole Christopher Pereira sadizeng Zachary Alstadt

And a shout-out to my top Ko-fi supporters!

Hung Hoang Arthur H Megan Taylor Takuya “Somebody”